We call this Keats’s “last” letter, but as with most things Keatsian, some uncertainty remains. And with any body of correspondence, what is left over must of necessity amount to less than the originary material. As they say in forensics, every contact leaves a trace. But not all traces persist, and the contacts always exceed their traces. So goes the phantasmal work of corresponding with Keats. He walks about our imaginations like a ghost, emerging into material, vivid fullness now and then, usually with a reminder of the absence that always haunts presence.

Keats himself draws this last letter to a close with a refusal of finality. “I shall write to XXX to-morrow, or next day,” he tells Charles Brown before issuing his utterly devastating awkward bow. He adds, “I will write to XXXXX in the middle of next week.” In all likelihood, though, he will not. If you were XXX or XXXXX, would you not have done all in your power to ensure that a letter written to you by Keats in his final months would survive into posterity? Given that no such letters exist, nor do any traces of them having ever existed, it’s safe to say that his future correspondence after 30 November 1820 was deferred indefinitely, and remains so. And yet, we persist in uncertainty, even if we know better.

The Xs in place of names gestures toward another bit of mystery connected with this last letter. The original manuscript is lost, as is the case with all but one of the extant letters to Brown (the letter of 30 September 1820 being the exception). The other eight letters come to us through Brown’s transcripts, made in his “Life of Keats” written between 1836 and 1841, and sent to Richard Monckton Milnes in March 1841. As he copied, Brown replaced the names of individuals with Xs, so we cannot know for sure to whom Keats intended to write (Rollins hazards guesses of Dilke and Woodhouse for the correspondents). More ghosts that haunt about the shape of the letter.

Brown clearly had difficulty revisiting the pain of two decades prior as he copied the nine letters then in his possession. In the letter accompanying his “Life of Keats” sent to Milnes, Brown writes, “Yesterday and to-day I have been occupied on this subject, and become fevered and nervous. I feel myself quite unable to fix my attention on these papers, whether in my hand writing or in his, any longer.” After passing on the “Life” to Milnes, Brown seems to have felt content that he was leaving the task of securing Keats’s place “among the English Poets” to a trusted steward. “A true friend of Keats,” he calls Milnes. The particular urgency of doing so at that moment for Brown, was that, as he posed it to Milnes, “I am on the eve of quitting England for ever.”

At the moment of consigning Keats’s final letter to its posthumous existence in Milnes’s care, Brown eerily parallels Keats back in 1820. Keats then found himself having left England for, what turned out to be, ever. And like Brown, he could hardly bear to fix his attention on the hand writing of “a friend I love so much as I do you,” as Keats wrote to Brown in this final letter of 30 November. Brown departed for New Zealand via The Oriental on 22 June 1841 and arrived in New Plymouth on 7 November. His life on Aotearoa did not last much longer than Keats’s in Italy: Brown died at New Plymouth on 5 June 1842.

One tantalizing question remains about the manuscript of this final letter: what did Brown do with it after copying it and sending the transcript to Milnes? Around the same time in 1841 when Brown sends Milnes the transcribed letters as part of his “Life of Keats,” he also sends some of Keats’s poetry manuscripts that were still in possession. He seems not to have ever intended to pass along the originals of any letters, so what became of them? Did he carry them with him across the oceans? Or did he perhaps–as Keats claimed, in a letter to Sarah Jeffrey, to have done in May 1819–make “a general conflagration of all old Letters and Memorandums”? An epistolary fire would certainly be one way to ease the pain of beholding Keats’s handwriting twenty years later. The future will determine whether any further traces of this last–or near-to-last–letter swim back into presence. For now, we have Brown’s copy and all the haunting resonances it summons into life.

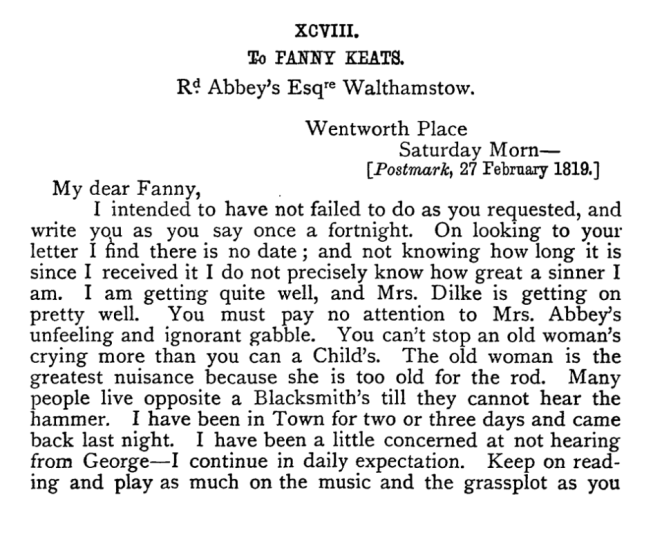

The manuscript of Brown’s “Life of Keats” now resides at Harvard’s Houghton Library, along with the vast majority of Milnes’s Keatsiana collected before and after his biography of Keats was first published in 1848. For a reliable nineteenth-century edition in the public domain, we recommend Harry Buxton Forman’s 1901 Complete Works. And images below show Brown’s transcript (via Houghton Library) and the text as it appears in Rollins’s edition (via Google Books).

The KLP will be publishing several different pieces commemorating this final letter, so stay tuned!

Page 1 of Brown’s transcript of Keats’s letter. Image courtesy Harvard University, Houghton Library.

Page 2 of Brown’s transcript of Keats’s letter. Image courtesy Harvard University, Houghton Library.

Page 3 of Brown’s transcript of Keats’s letter. Image courtesy Harvard University, Houghton Library.