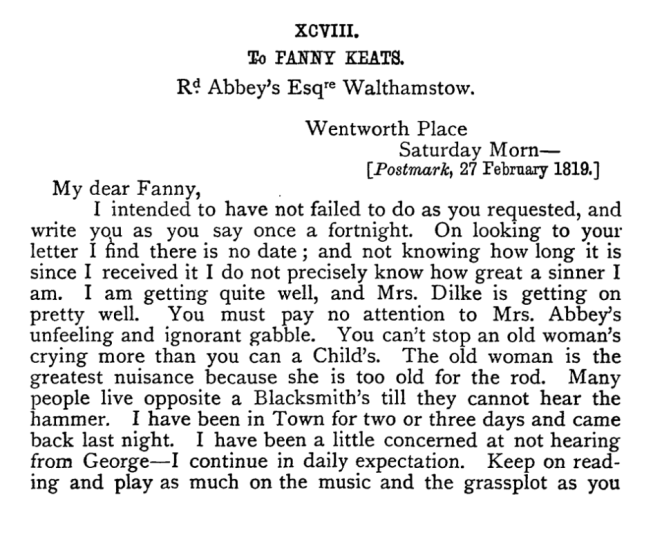

Keats continues to uphold his efforts to write his sister on a biweekly basis, and although he worried that he’d lost track of time and been truant, turns out he was only off by two days (his last letter to her was on 11 February). Not too shabby. As in that previous letter, Keats empathizes with Fanny’s disappointment about her current living situation. Back on the 11th, Keats bemoaned that her guardian Richard Abbey removed Fanny from her school (The Ladies Boarding Academy run by Mary Ann and Susanna Tuckey at 12 Marsh Street in Walthamstow). Today Keats focuses on Mrs. Abbey.

It appears that Fanny had complained to her brother about Mrs. Abbey’s “unfeeling ignorant gabble.” We don’t know exactly to what that refers, but it seems at least possible that Mrs. Abbey may have been speaking ill of Fanny’s brothers. We know that Mr. Abbey tried to keep Fanny apart from the young men whom he deemed to be bad influences (a poet and an American adventurer, yikes!). Perhaps Mrs. Abbey had some negative “gabble” to say about the brothers as well. In any case, it seems Fanny indicated that Mrs. Abbey’s “crying” was constant. Keats advises that Fanny persevere: “Many people live opposite a Blaksmith’s till they cannot hear the hammer.”

Another topic of significance is one that we’ll hear more about over the course of this year. Keats notes that “I have been a little concerned at not hearing from George–I continue in daily expectation.” Turns out that the 19th-century transatlantic postal system could be a bit unreliable! Particularly in Keats’s letters to George and Georgiana, we find him frequently bemoaning the uncertainty of epistolary communication across the ocean. As a contrast to that span of distance and time, Keats closes today’s letter to Fanny with a more felicitous notion of letter writing: “Write me directly and let me know about them [the status of Fanny’s chilblains]–Your Letter shall be answered like an echo–“

Now we’ll let that echo reverberate and encourage you to read the letter to Fanny in Forman’s 1901 edition. Images below via HathiTrust.